Job quality

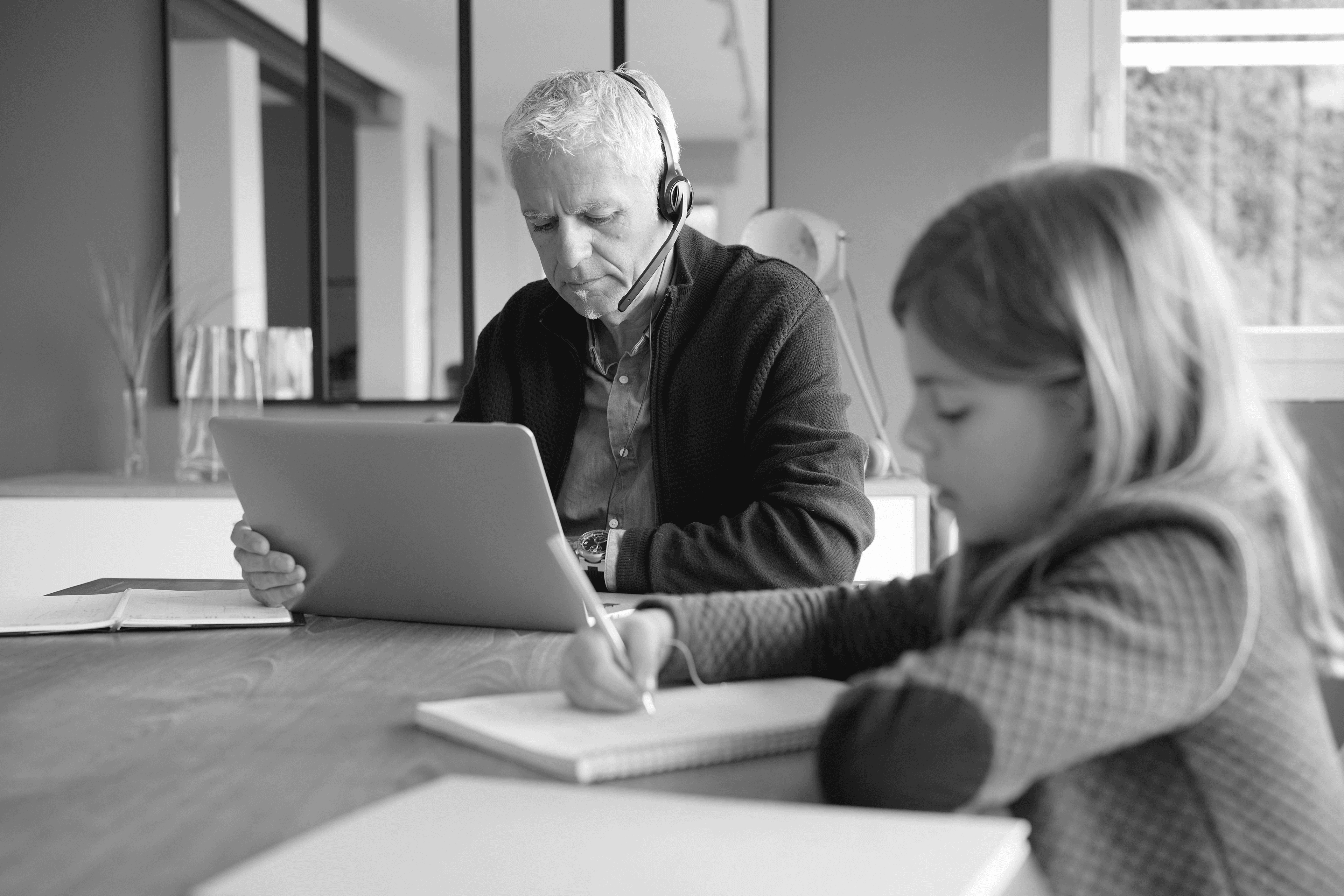

The COVID-19 pandemic had profound implications on the labour market and job quality in Europe, with some workers, particularly those providing frontline services, continuing to work from the workplace under heavy restrictions, while others worked from home also in radically different environments from which they were accustomed. Eurofound has been closely monitoring working conditions in Europe for over 30 years via the European Working Conditions Survey; in 2021, the Agency conducted the European Working Conditions Telephone Survey (EWCTS), providing a detailed picture of the working lives of Europeans at an exceptional time. In this episode of Eurofound Talks, Eurofound Head of Unit for Working Life Barbara Gerstenberger discusses what the EWCTS reveals about job quality, the implications of poor-quality jobs on well-being and broader society, and what policymakers can do to improve the working lives of people in Europe.

Listen to this episode

You can listen to this episode below or on the podcast platform of your choice.

Ομιλητές επεισοδίου

Mary McCaughey

Head of UnitΗ Mary McCaughey είναι επικεφαλής πληροφόρησης και επικοινωνίας στο Eurofound. Απόφοιτος του Trinity College του Δουβλίνου και του Κολλεγίου της Ευρώπης της Μπριζ, ξεκίνησε να εργάζεται στις Βρυξέλλες με την Europolitics και την Wall Street Journal Europe. Συνεργάστηκε με την Ένωση Ευρωπαίων Βουλευτών με την Αφρική (AWEPA) στη Νότια Αφρική κατά τη διάρκεια της μετάβασης της χώρας στη δημοκρατία και το 1998 ανέλαβε τη θέση της εκπροσώπου τύπου της Αντιπροσωπείας της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης στην Πρετόρια, επικεφαλής του τμήματος Τύπου και Πληροφοριών κατά τη διάρκεια των διαπραγματεύσεων για τη συμφωνία ελεύθερων συναλλαγών ΕΕ-Νότιας Αφρικής. Μετά το τέλος του πολέμου του Κοσσυφοπεδίου, εργάστηκε ως σύμβουλος επικοινωνίας για την Ευρωπαϊκή Υπηρεσία Ανασυγκρότησης στη Σερβία. Ανέλαβε καθήκοντα αρχισυντάκτριας στο Eurofound το 2003.

Barbara Gerstenberger

Head of UnitΗ Barbara Gerstenberger είναι επικεφαλής της μονάδας «Εργασιακός βίος» του Eurofound. Από τη θέση αυτή, συντονίζει τις ερευνητικές ομάδες που διερευνούν την ποιότητα των θέσεων εργασίας στην Ευρώπη με βάση την Ευρωπαϊκή Έρευνα για τις Συνθήκες Εργασίας και έχει τη γενική ευθύνη για το Ευρωπαϊκό Παρατηρητήριο του Εργασιακού Βίου και την έρευνα για τις εργασιακές σχέσεις στην ΕΕ. Εντάχθηκε στο Eurofound το 2001 ως διευθύντρια έρευνας στο νεοσύστατο τότε Ευρωπαϊκό Παρατηρητήριο της Αλλαγής (EMCC). Το 2007 μετακινήθηκε στη μονάδα πληροφοριών και επικοινωνίας του Eurofound ως προϊσταμένη προϊόντων επικοινωνίας, προτού διοριστεί συντονίστρια στη διεύθυνση το 2011. Προηγουμένως, εργάστηκε ως ανώτερη ερευνήτρια στην Ευρωπαϊκή Ομοσπονδία Μεταλλουργών στις Βρυξέλλες. Απόφοιτος πολιτικών επιστημών από το Πανεπιστήμιο του Αμβούργου, ολοκλήρωσε μεταπτυχιακό στη Δημόσια Διοίκηση στο Kennedy School of Government του Πανεπιστημίου του Χάρβαρντ.

Recently published episode

)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)