More attention must be given to Europe’s working poor

In-work poverty increased during the economic and financial crisis that hit European shores in 2008. By 2014, ten per cent of European workers were at risk of poverty, up from eight per cent in 2007. Ten per cent is a significant figure: the working poor represent a substantial group that can’t be ignored. Just as disconcerting is the finding that 13 per cent of European workers are materially deprived. This latter measure helps to capture the impact of the crisis on people’s real living conditions.

Eurostat: In-work at risk of poverty rate

A new study by Eurofound looks at what it means to be working poor and finds that in-work poverty is associated with lower levels of subjective and mental well-being, problems with accommodation, as well as poorer relationships with other people and feelings of social exclusion. This demonstrates the importance of paying particular attention to the working poor and of better documenting their social situation.

Much of the focus of governments and social partners is on getting people into work. However, having a job is not always enough to avoid poverty and in many European Union member states the number of working poor households increased during the economic and financial crisis. If no attention is paid to the incomes these workers receive and the nature of the households in which they live, this could even further increase the amount of people at risk of in-work poverty in Europe.

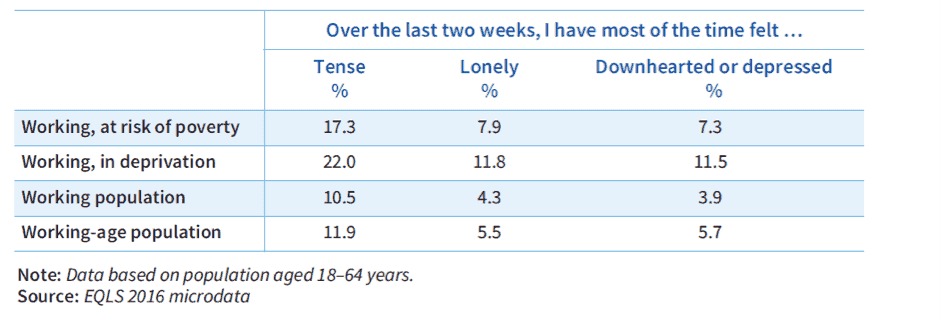

An outcome of the crisis has been an increase in mental health problems. Data from Eurofound’s 2016 European Quality of Life Survey shows that the working poor are more likely to report mental health problems than the working population in general: 22 per cent of those experiencing material deprivation reported having felt tense and 12 per cent felt lonely or downhearted and depressed. For the working population at large the figures are significantly lower.

Workers experiencing material deprivation are also less likely to have somebody with whom to discuss personal matters and they receive less help from relatives, friends or neighbours than their non-poor counterparts. They are also more likely to feel unrecognised by others or to say that people look down on them due to their job situation or income. Twelve per cent say they feel left out of society, compared to five per cent for the working population at large. This suggests that perceived social exclusion is a significant problem among working poor Europeans.

Housing trap

Another issue for the working poor is poor quality housing, with all the associated risks this has with poor health. Compared to the working population at large, the working poor are nearly twice as likely to live in an overcrowded household or in a dwelling that is too dark. The cost of housing is also a serious problem for the working poor: 2014 data from Eurostat shows that for seven out of ten materially deprived workers, housing costs are a heavy burden. What is striking about this is that of all the measures examined, the cost of housing is the only one where the working-poor score even worse than the unemployed, for whom housing allowances provide some assistance.

The recorded inequalities in the living conditions of the working poor go beyond accommodation alone; it also relates to their immediate living environment. In addition to reporting lower satisfaction with the recreational or green areas in their neighbourhood, materially deprived workers more frequently report crime, violence or vandalism in their immediate environment, more pollution and more noise.

Finally and not surprisingly, working poor Europeans rate their life satisfaction lower than better-off workers.

All of this shows that in-work poverty has serious social ramifications. That is why measures are needed that aim directly at helping to improve the living standards of this group of Europeans. This can be achieved not only through direct measures such as better income support and better social protection but also through indirect measures like access to childcare and housing support. As the study shows, ignoring the situation of this significant group of European workers has serious societal implications.

Related links

Publication: In-work poverty in the EU

Publication: Inadequate housing in Europe: Costs and consequences

Author

Daphne Ahrendt

Senior research managerDaphne Ahrendt is a senior research manager in the Social Policies unit at Eurofound. She is the coordinator of the survey management and development activity. In 2020, she initiated Eurofound’s Living and Working in the EU e-survey and now leads the 2026 European Quality of Life Survey, which she has worked on since the survey started in 2003. With over 30 years of experience in international survey research, she is also a member of the GESIS Scientific Advisory Board. Beyond surveys, her substantive research focuses on social cohesion, trust and the inclusion of persons with disabilities. Daphne started her career at the National Centre for Social Research in London where she worked on the International Social Survey Programme before moving to the Eurobarometer Unit at the European Commission. She holds a Master's degree in Criminal Justice Policies from the London School of Economics and a Bachelor's degree in Political Science from San Francisco State University.

Related content

5 September 2017

The ‘working poor’ are a substantial group, the latest estimate putting 10% of European workers at risk of poverty, up from 8% in 2007. This report describes the development of in-work poverty in the EU since the crisis of 2008, picking up where an earlier Eurofound report on this subject, published in 2010, ended and looks at what countries have done to combat the problem since. This endeavour is complicated by the policy focus on employment as a route out of poverty, underplaying the considerable financial, social and personal difficulties experienced by the working poor. The increase in non-standard forms of employment in many countries appears to have contributed to rising in-work poverty. The report argues the case for greater policy attention and action on the part of governments, employers and social partners, not only through direct measures associated with both the minimum and living wage, progressive taxation, in-work benefits and social assistance, but also and more importantly through indirect measures such as more flexible working arrangements, housing, upgrading of skills and childcare.

4 August 2016

This report aims to improve understanding of the true cost of inadequate housing to EU Member States and to suggest policy initiatives that might help address its social and financial consequences. The full impact of poor housing tends to be evident only in the longer term, and the savings to publicly funded services, the economy and society that investment in good quality accommodation can deliver are not always obvious. While housing policies are the prerogative of national governments, many Member States face similar challenges in this field. In some, projects to improve inadequate housing have already provided valuable practical experience that can usefully be shared, and this report presents eight such case studies. While improving poor living conditions would be costly, the report suggests the outlay could be recouped quite quickly from savings on healthcare and a range of publicly funded services – in the EU as a whole, for every €3 invested in improving housing conditions, €2 would come back in savings in one year.

With contributions from Robert Anderson, Pierre Faller, Jan Vandamme (Eurofound) and Madison Welsh.