Germany’s minimum wage has reduced wage inequality

Wages grew and wage inequality fell in most EU countries in 2015. Germany is not one of the countries where wages rose most, but it did have the largest reduction of wage inequality. Our analysis shows that the German minimum wage policy introduced in 2015 strongly lifted the wages of the lowest-paid employees, particularly those employees who were lower-skilled, younger or working in services.

Wages and wage inequality are a topic of intense debate among academics and policymakers in Europe. Before the crisis, the discussion centred on wage growth below productivity levels and widening pay differentials across the workforce.

More recently, it has turned to big wage declines in some European countries severely hit by the crisis and the sluggish recovery of wages. But analysis of the most recent micro-data from the EU-SILC survey, for 2015, shows a reversal of negative trends in many EU Member States.

Wages rise and wage inequality falls

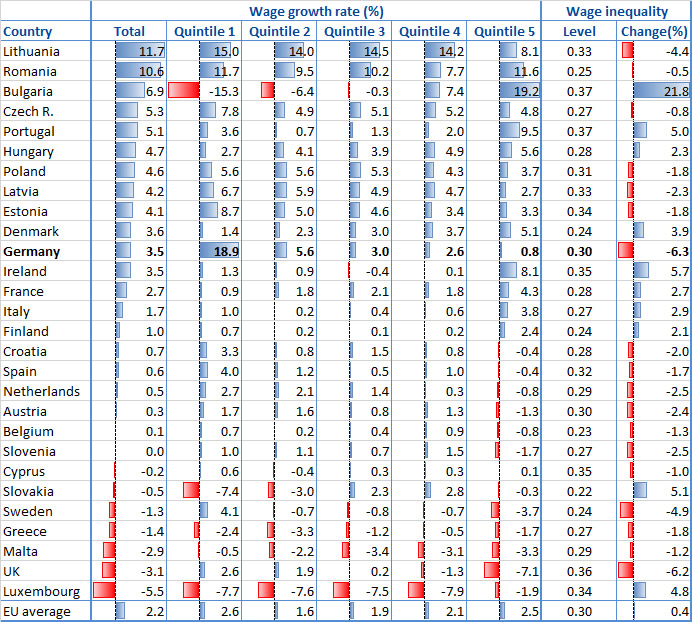

Average real wages increased in more than two-thirds of EU countries in 2015, but there are substantial differences across the region (see the first column in the table below). Wages grew in most eastern European countries and to a much greater extent than in most western European countries, where wage growth was rather subdued or even negative, especially in Mediterranean countries; exceptions were Denmark, Germany, Ireland and France. Similarly, wage inequality declined in around two-thirds of EU countries (see the last column in the table), although there is no significant association between the changes in average wage levels and in wage inequality levels.

Three main patterns emerge from the analysis:

Strong wage growth (4%–12%), mainly due to wages improving more among the lowest-paid employees (quintile 1), causing a fall in wage inequality. We see this pattern in much of eastern Europe – the Baltic countries, the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania – although not in Bulgaria, especially, nor Hungary, where wages grew more among the higher-paid.

More moderate wage growth (1%–3%), mostly due to wage increases among the highest-paid employees, leading to hikes in wage inequality. This is apparent in Denmark, Ireland, France, Italy and Finland.

Wage declines or stagnation (growth of 1% or less) alongside falls in wage inequality generally, mainly due to wage reductions among the highest-paid (Quintile 5). The table shows this pattern in most countries from Croatia down, most significantly in Sweden and the UK.

Germany is similar to the second group of countries because real wages grew significantly (3.5%), although below the rates of eastern European countries. But growth over the wage distribution is completely different in this case: wages increased disproportionately among the lowest-paid employees (by almost 20% in wage quintile 1), which explains why Germany registered the largest reduction in wage inequality among all EU countries in 2015.

Change in average real wages by wage quintile and change in wage inequality, EU Member States, 2015

Note: Countries are ranked by the magnitude of the wage growth.

Source: EU-SILC

Impact of Germany’s minimum wage policy

The marked increase of wage levels among the lowest-paid employees in Germany can only be explained by the introduction of a minimum wage in 2015. This was a major policy decision aimed at fighting the rising numbers of employees not covered by wage floors and the growth of low-paid work in the country. Our analysis of the data shows this policy decision introduced a significant break in the wage dynamics of the German labour market, where wage inequality had expanded in 2014.

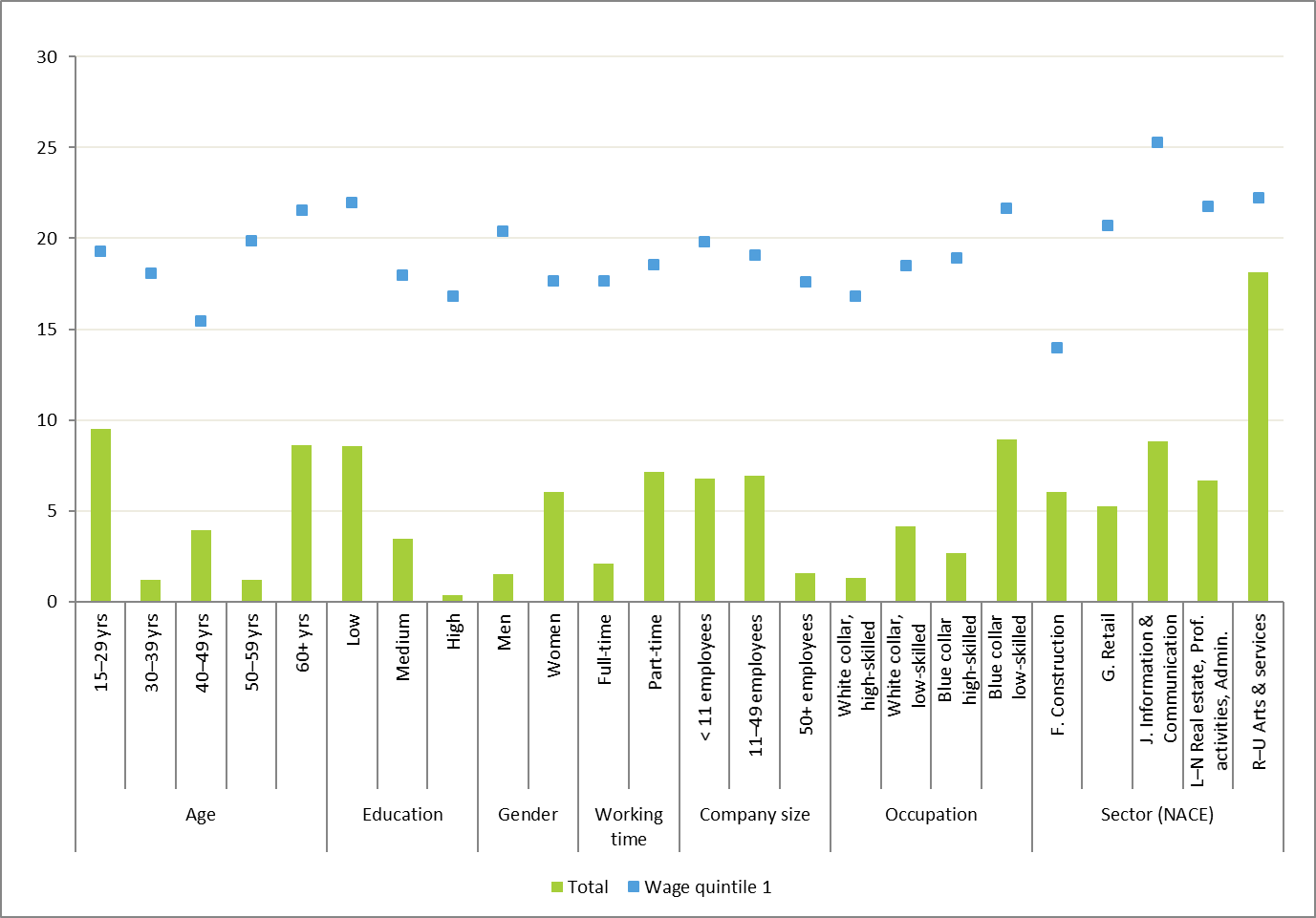

Some groups within the workforce benefited more from this development than others. As the figure below illustrates, wage gains were significantly higher among the youngest and oldest age groups; employees with lower educational attainment; female employees; part-time employees; employees working in smaller companies; and employees in low-skilled occupational categories (blue collar especially but also white-collar to a lesser extent). In terms of economic sector, employees working in services benefited greatly. For instance, those working in arts, entertainment and recreation saw the highest wage boost, although employees in other service sectors – including information and communication, and real estate, professional and administrative activities – also saw substantial gains. Increases among employees in construction and retail, though lower, were still higher than average.

The main reason why the relative wage increase among these groups of employees was much higher is because they are more typically found at the bottom of the wage distribution, which is where the minimum wage policy had the biggest impact. This explains why when we look at the wage growth specifically among employees in the bottom quintile of the wage distribution – comparing the levels of the blue dots in the figure – the disparities dependent on employee characteristics (age, education, gender and so on), although still present, tend to become more modest. For example, the relative disparities between employees of different age groups in wage quintile 1 (blue dots) are less than the disparities between age groups in the total population of employees (green bars).

Relative change in average real wage levels (total and in wage quintile 1) by employee characteristics, Germany, 2015 (%)

Source: EU-SILC

Moreover, the beneficial effects of the minimum wage policy on real wage growth and the wage cohesion of the German workforce seem to have come at no significant price. Employment data show the employment prospects of those employees who have benefited more from the introduction of the minimum wage have not deteriorated, proving that fears about the potential disemployment effects of the policy were exaggerated.

For more detail on this analysis, see the working paper Wage developments in the EU and the impact of Germany’s minimum wage.

Image: © Shutterstock/Africa Studio

Author

Carlos Vacas‑Soriano

Senior research managerCarlos Vacas Soriano is a senior research manager in the Employment unit at Eurofound. He works on topics related to wage and income inequalities, minimum wages, low pay, job quality, temporary employment and segmentation, and job quality. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2010, he worked as a macroeconomic analyst for the European Commission and as a researcher in European labour markets at the Spanish Central Bank. He holds an MA in European Economic Studies from the College of Europe in Bruges and a PhD in Labour Economics from the University of Salamanca (Doctor Europaeus).

Related content

6 February 2018

The term ‘minimum wage’ refers to the various legal restrictions governing the lowest rate payable by employers to workers, regulated by formal laws or statutes. This report provides information on statutory minimum wages that are generally applicable in a country and not limited to specific sectors, occupations or groups of employees. While the scope of the report covers all 28 EU Member States, the main findings relate to the 22 countries that had a statutory minimum wage in place in 2018. In the majority of countries, the social partners have been involved in the setting of the minimum wage in 2018 – in marked contrast to the beginning of the decade when minimum wage-setting was characterised by strong government intervention. While the highest increases in the minimum wage were recorded (in nominal and real terms) in Bulgaria and Romania, both of these countries – as well as several others – have a long way to go to catch up with the minimum wage levels prevailing in western European countries.